Robyn Roche-Paull, BSN, RNC-MNN, IBCLC

Tips and tricks to make pumping as stress free and effective as possible.

Expressing your breast milk is one way of connecting with your baby when you must be separated. It provides him with your precious milk, along with all the antibodies and nutrition that are so important for his growth and development; but more than that, it also keeps your milk supply up, so you can breastfeed and remain close when you are together. However, pumping is not a natural process. We are not meant to be hooked up to a machine. It can take time and a bit of a learning curve to get the hang of it and do it well.

Getting started

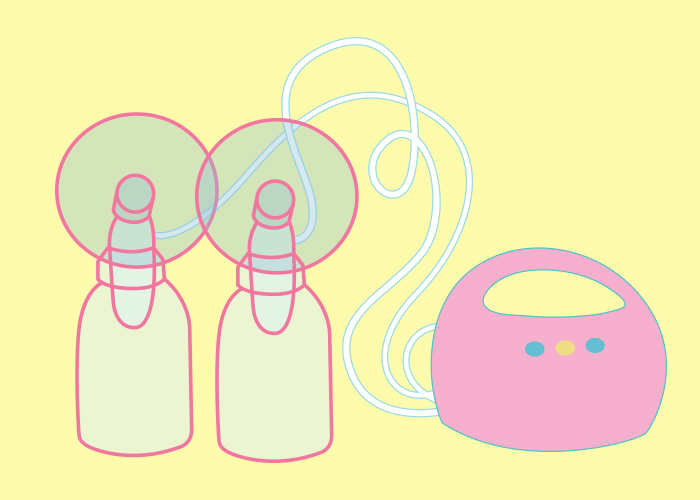

Depending on when you need to return to work, you may want to start pumping about four to six weeks before your maternity leave ends. Begin by pumping in the mornings, when your supply is at its highest. Center your nipple in the breast flange (some mothers find that lubricating the flange with water or olive oil helps to create a stronger seal and reduces friction). Then start the pump. When using an automatic pump, turn it to its lowest setting and gradually increase the speed and suction. With a manual pump, start with a gentle, slow rhythm. Set the pump to the maximum comfortable setting for you. Pumping should not be painful. If it hurts, something is wrong. Continue pumping for about 15 minutes or around two minutes past the last drops. With pumping, frequency is more important than duration for building and maintaining a good milk supply.

frequency is more important than duration for building and maintaining a good milk supply.

Pumping is a skill that you learn and it takes time to master it. Do NOT be alarmed if you get only drops or even nothing at all the first few times. Expressing your breast milk with a pump is as much a psychological process as it is a physical one. Your body is used to letting-down to a warm, cuddly baby and is trying to get used to letting-down to a cold, hard plastic pump instead. With time and practice, it will become second nature and you’ll be pumping like a pro!

Maximize your production

After pumping regularly for a while you may find that your milk supply is dwindling. A low supply of breast milk can be caused by numerous factors, but is most often from a lack of time to pump during the work day. Keep in mind that even the best breast pump on the market can never remove milk as effectively as your baby, and milk supply varies throughout the day and from day to day, so dips in supply are more noticeable when pumping than when breastfeeding.

Follow these tips to maximize your production when expressing your breast milk.

- Don’t skip pumping sessions! Aim for 8–10 breastfeeding/pumping sessions in 24 hours and double pump (that’s both breasts) for 15–20 minutes or about two minutes past the last drops. Pump at least every 3–4 hours while at work. Full breasts signal your body to slow/stop milk production. With pumping, frequency is more important than duration.

- Breastfeed or pump at least once at night. Prolactin, a milk-making hormone, peaks during the nighttime hours, increasing your overall milk supply. Try to breastfeed or pump at least once between midnight and 5 am.

- Power pumping. Power pumping is very effective at boosting production. Try pumping for the length of each commercial break during your favorite TV show. Pump for just 5 minutes with many sessions sprinkled throughout the day. Take a “pumping vacation”: for 2–3 days pump after every breastfeeding session.

- Establish a routine. Pumping is as much about your brain as it is your breasts. Try to pump in the same place and at the same time every day to condition your let-down reflex.

- Stimulate a let-down. Along with establishing a routine, you might try the following when you pump:

- Relax shoulders

- Deep breathing

- Apply warmth to breasts (hot packs)

- Massage breasts before pumping

- Visualize “rivers of milk”

- Smell a piece of your baby’s clothing or blanket

- Listen to a recording of your baby’s sounds (crying, laughing, babbling)

- Watch a video of your baby breastfeeding (taken over your shoulder)

- Pump with a buddy. Don’t be shy, pumping with a friend or co-worker increases oxytocin, resulting in higher milk yield during your pumping session for both of you!

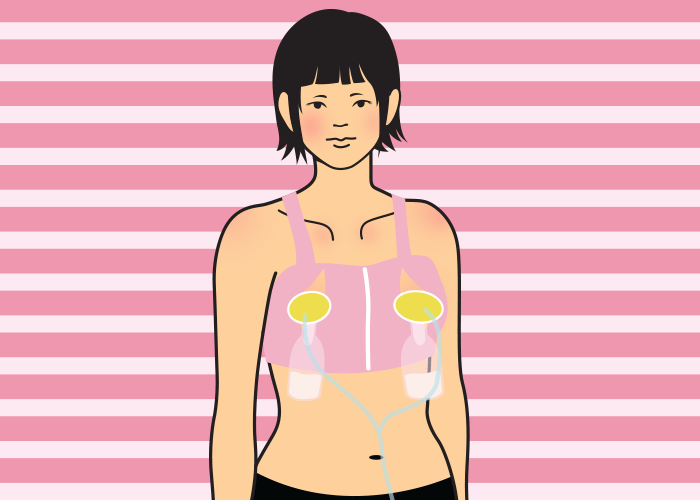

- Pump during your commute. If you have a long commute, consider using a hands-free bra so you can pump during your drive. This can add two more pumping sessions to your day and can really boost your supply.

- Breastfeed at drop-off and pick-up from day care. Breastfeed your baby at day care to add more sessions at the breast for increased stimulation. This is really important if you have a long commute or can’t pump often at work. Ask your day care provider to hold off feeding your baby an hour before pick-up so you can feed before heading home.

- Hands-On Pumping (HOP). HOP is a well-researched way to increase your production and is very simple to do. Massage breasts before pumping, and do breast compressions during pumping. Finish by hand expressing for a minute or two after pumping. HOP empties the breasts better and has been shown to increase milk yield by up to 48%, as well as doubling the fat of expressed milk. View these videos on HOP.

- Tandem pump while breastfeeding. By putting your baby on one breast and pumping the other breast at the same time, you can double your stimulation and capture more milk for later use.

- Adjust settings on pump. Change things up a bit: consider pressing the let-down button or changing the suction and frequency settings on your pump throughout your pumping session. Babies usually trigger 2–3 let-downs when they breastfeed, you should mimic the same when pumping. Make sure to set suction to your maximum comfort level for best output.

- Rent a hospital-grade pump. If you’ve hit a rut, you might consider renting a hospital-grade pump for a few weeks to increase your milk supply. The change in motor strength and cycling frequency can be enough to jump-start your supply again.

- Alternate flange sizes. Are your flanges (shields/horns) the correct size? Switching to a smaller or larger pump flange can make a big difference in pumping comfort and/or output. You may also want to look into angled Pumpin’ Pals Super Shield flanges or soft-inserts that “massage” the breast if you find your flanges don’t fit properly. See an IBCLC to be fitted correctly.

- Galactagogues. Your body may need a boost that can only be created by herbs or medications. Speak with an IBCLC about which ones are best in your situation before running out to the store. Herbs are a medication and should not be taken without proper precautions and supervision, especially if you or your baby have any underlying medical conditions.

- Do NOT watch the collection bottles. Watching the bottles while you pump can be a self-fulfilling prophecy, as you worry about your output and then don’t see any milk. Cover your flanges and bottles with a blanket when pumping and concentrate on a video of your baby or playing a mindless game on your phone while pumping. Before you know it the bottles will be full of milk!

Time-savers

Sometimes just shaving a few minutes off your pumping routine is what you need to do to make it through the work day, or keep your boss off your back about pumping. Try adding some of the following to your routine:

- Invest in a hands-free bra. A hands-free bra, either store bought or home made, offers you the ability to complete tasks while at work (such as charting on a computer) but also allows you to do hands-on pumping which increases milk yield. There are two ways to make your own hands-free bra:

- Cut slits in a criss-cross pattern over the nipple area in a sports bra

- Use rubber bands to make a hands-free bra (for instructions and photos click here)

- Extra flanges. Have 2–3 sets of flanges and tubing at work. Use a new set with each pumping session. Wash all of them at night when you get home.

- Refrigerate your parts. Another option is to refrigerate your flanges between pumping sessions, and wash them all when you get home. The cold reduces bacterial growth and the milk expressed is considered safe for a full-term healthy infant.

- Partner help. Your partner can wash your pump parts and get your pump ready for the next day, so you can sit on the couch and breastfeed. The extra time your baby is at the breast will boost your production.

Troubleshooting tips

There may be times when you are doing everything right to increase and maximize your milk production, but it’s just not working. You might have started a new medication or the membranes on your pump need replacing. Take a glance through the following checklist to determine if the decrease in your pumping output is due to you or your pump.

Is it you?

Sometimes a dip in supply when pumping is due to personal factors:

- Hormonal birth control methods can cause lowered milk supply, especially those with estrogen in them, as can Depo-Provera. Some mothers are even sensitive to the hormones in the mini-pill or Mirena IUD. Check with your doctor for options if you feel this is impacting your milk supply.

- Medications, such as decongestants used for the common cold, can cause lowered milk supply in up to 20% of women who take them.

- Growth spurts. Is your baby asking to breastfeed a whole lot more than usual? If so, he may be having a growth spurt and is building up your supply. Growth spurts are normal at around 2 weeks, 6 weeks, 3 months, and 6 months. Be prepared and breastfeed as much as possible when you are together. Consider adding in a few extra pumping sessions as well.

- Illness. If you have you been sick lately with a cold or the flu, you may find that your milk supply is down a bit. Increased breastfeeding, lots of fluids, and rest should bring it right back up.

- Overfeeding is a common culprit, especially at day care. Bring your milk in small quantities (2–4 ounces), and teach your provider “Paced-bottle feeding,” which means holding the baby, giving small, frequent feeds, and watching the baby for feeding cues. Give your provider this information about how to bottle-feed the breastfed baby.

- Pacifiers. If you use a pacifier a lot when you are together, you may be sabotaging your milk supply inadvertently. Every time you use a pacifier instead of breastfeeding, that is one less time your breasts are stimulated to make milk. Only use pacifiers when you are apart. When you are together, breastfeed!

- Period or pregnancy. Has your period returned? Could you be pregnant? Hormones can cause a lowered milk supply in the week leading up to your period or during pregnancy.

- Sleeping through the night. If your baby has started sleeping through the night, you may find your milk supply has taken a nosedive. The hormones responsible for making milk are at their highest during the nighttime hours and breastfeeding at night boosts those hormones, which in turn boosts your supply. If your baby is sleeping through the night, you are missing out on that boost. Consider pumping at least once at night, or look into “reverse-cycle feeding” (i.e. breastfeeding your baby through the nighttime hours, which is easier while co-sleeping or bedsharing).

- Stress. If you are stressed, it can affect your milk supply—who isn’t stressed when working and pumping? Breastfeeding produces a naturally occurring relaxing hormone. After work, sit on the couch to enjoy that down-time with your baby. Let the hormones do the trick to relax you both after a long day.

Is it your pump?

Trouble with your pump can also cause milk supply issues:

- Proper pump. Is your pump appropriate for the amount of pumping that you do? An occasional-use pump is not meant for hardcore use, 3–5 times a day, by a working mother. Invest in the proper pump for your needs. Check out How to Choose a Breast Pump for more information on what to look for in a breast pump.

- Age. How old is your pump? Breast pump motors are generally under warranty for one year. The motors in pumps older than a year often start to wear out, especially if you are pumping more often than the pump was designed for. This can lead to ineffective pumping and a lowered milk supply. Have your pump’s suction tested by an IBCLC.

- Maintenance. Do your pump parts need to be replaced? Check your pump and replace any parts that are worn or that haven’t been replaced in the last 3–6 months. Check tubing for leaks or holes, and membranes for tears. A little preventive maintenance often fixes pump problems ASAP.

- Used pump. Are you using a used pump? A used pump’s motor may be dying, leading to lowered milk output. If your pump is not a closed system pump, designed for multiple users, it may be harboring mold, bacteria, or viruses on the parts that cannot be sterilized. Buy a new pump, not just new flanges and tubing. The cost of a good pump is about the same as two months of formula, but will provide your baby with your breast milk for a year or more. In the United States, insurance companies are required to provide you with a breast pump free of charge.

Pumping for your baby takes a huge commitment. You should feel very proud of your accomplishment, no matter how much or how little milk you can express to provide for your baby. Remember, that while providing your milk is important, your breastfeeding relationship is more important. Pumping while you are separated allows you to be able to breastfeed when you are together to keep that connection between you strong.

Robyn Roche-Paull, BSN, RNC-MNN, IBCLC, is the award-winning author of the book, Breastfeeding in Combat Boots: A Survival Guide to Successful Breastfeeding While Serving in the Military and the Executive Director of the non-profit, Breastfeeding in Combat Boots.

Hand-operated pumps

Hand-operated pumps

Cycles and suction settings

Cycles and suction settings Adapters and batteries

Adapters and batteries

I was living in Japan when I was pregnant with my first child and I knew few other mothers. Although I had a normal pregnancy, an extremely medicalized antenatal system meant I had lots of scans and a vaginal examination at every check-up. Pregnancy was treated like a dangerous condition. No wonder then that I developed a level of distrust about my own body. “I’d like to breastfeed, if I can,” I thought, but as a first time mother, I felt untested. Would my breasts work or would they need a bit of help? I got a hand pump “just in case.”

I was living in Japan when I was pregnant with my first child and I knew few other mothers. Although I had a normal pregnancy, an extremely medicalized antenatal system meant I had lots of scans and a vaginal examination at every check-up. Pregnancy was treated like a dangerous condition. No wonder then that I developed a level of distrust about my own body. “I’d like to breastfeed, if I can,” I thought, but as a first time mother, I felt untested. Would my breasts work or would they need a bit of help? I got a hand pump “just in case.”

Alice Allan grew up in rural Devon then studied English at Cambridge University. She worked as an actress and a corporate trainer in London and Tokyo, then as a lactation consultant in public hospitals in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, where she taught about breastfeeding, skin-to-skin and kangaroo care for premature babies. She has written for a number of publications including The Telegraph, The Sunday Express, the Ethiopian Herald, The Green Parent and The Mother Magazine. She currently lives in Tashkent, Uzbekistan with her diplomat husband, two daughters and a large Ethiopian street dog called Frank.

Alice Allan grew up in rural Devon then studied English at Cambridge University. She worked as an actress and a corporate trainer in London and Tokyo, then as a lactation consultant in public hospitals in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, where she taught about breastfeeding, skin-to-skin and kangaroo care for premature babies. She has written for a number of publications including The Telegraph, The Sunday Express, the Ethiopian Herald, The Green Parent and The Mother Magazine. She currently lives in Tashkent, Uzbekistan with her diplomat husband, two daughters and a large Ethiopian street dog called Frank.

Like many women out there, Tracey Montford is an exceptional multi-tasker! Apart from steering a global business, managing 2 young boys and keeping the clan clean and fed, Tracey still finds time to provide creative inspiration and direction to the exceptional designs of Cake Maternity. From the branding, presentation and delivery, creativity is a big part of what Tracey does so naturally and effectively. Find out more at

Like many women out there, Tracey Montford is an exceptional multi-tasker! Apart from steering a global business, managing 2 young boys and keeping the clan clean and fed, Tracey still finds time to provide creative inspiration and direction to the exceptional designs of Cake Maternity. From the branding, presentation and delivery, creativity is a big part of what Tracey does so naturally and effectively. Find out more at

Ted Greiner PhD

Ted Greiner PhD

Chris Auer is a registered nurse and lactation consultant who has worked at the University of Cincinnati Medical Center for 42 years caring for mother-baby pairs from all walks of life and from as many as 77 countries, particularly those within a high risk demographic and in a Level III NICU setting. For over 20 years, Chris has provided pediatric resident lactation education and internship training and has published articles in seven peer-reviewed journals. Under One Sky is available

Chris Auer is a registered nurse and lactation consultant who has worked at the University of Cincinnati Medical Center for 42 years caring for mother-baby pairs from all walks of life and from as many as 77 countries, particularly those within a high risk demographic and in a Level III NICU setting. For over 20 years, Chris has provided pediatric resident lactation education and internship training and has published articles in seven peer-reviewed journals. Under One Sky is available

Being an ultra runner has given me the ability to believe in the impossible. Reading about how other élite runners had managed to get back into running after having a baby gave me confidence and I became a member of a wondeful support group called “Running Pregnant/While-Nursing – Moms Run This Town.”

Being an ultra runner has given me the ability to believe in the impossible. Reading about how other élite runners had managed to get back into running after having a baby gave me confidence and I became a member of a wondeful support group called “Running Pregnant/While-Nursing – Moms Run This Town.” By August, I had worked up to a 20-mile run. That was the first time I’d stopped to pump my breast milk in the car, half way round. Pumping was an interesting element to add to my training! I couldn’t just go out and run whenever or wherever I wanted. I had to think about how long I would be running and plan ahead when and where to pump. I also had to re-figure fueling my long runs to make sure I was drinking and eating enough for training and for making milk. I struggled a lot

By August, I had worked up to a 20-mile run. That was the first time I’d stopped to pump my breast milk in the car, half way round. Pumping was an interesting element to add to my training! I couldn’t just go out and run whenever or wherever I wanted. I had to think about how long I would be running and plan ahead when and where to pump. I also had to re-figure fueling my long runs to make sure I was drinking and eating enough for training and for making milk. I struggled a lot

In the late morning, I finally made it. About half a mile from the finish, I saw my family waiting for me to come in. My baby was in a stroller and I took it and ran with her towards the finish line. Before going into the finish chute, I took her out of the stroller and carried her across the finish line while my many friends cheered. I’d completed 100 miles in

In the late morning, I finally made it. About half a mile from the finish, I saw my family waiting for me to come in. My baby was in a stroller and I took it and ran with her towards the finish line. Before going into the finish chute, I took her out of the stroller and carried her across the finish line while my many friends cheered. I’d completed 100 miles in

Pamela Morrison lived the first 45 years of her life in East and Southern Africa. She has worked with breastfeeding mothers since 1987 and became the first IBCLC in Zimbabwe in 1990. She has also lived in Australia and is now living in England. She has been a long-term member of the Zimbabwean National Breastfeeding Committee, the BFHI Task Force and Co-coordinator of the WABA Task Forces on Infant Nutrition Rights, Breastfeeding and HIV. Pamela supports mothers to breastfeed and specialises in helping with latching difficulties, babies with low weight gain and faltering growth and mothers who are struggling to make enough milk. Pamela speaks passionately on breastfeeding and is a well-loved mentor and friend to many in the lactation field.

Pamela Morrison lived the first 45 years of her life in East and Southern Africa. She has worked with breastfeeding mothers since 1987 and became the first IBCLC in Zimbabwe in 1990. She has also lived in Australia and is now living in England. She has been a long-term member of the Zimbabwean National Breastfeeding Committee, the BFHI Task Force and Co-coordinator of the WABA Task Forces on Infant Nutrition Rights, Breastfeeding and HIV. Pamela supports mothers to breastfeed and specialises in helping with latching difficulties, babies with low weight gain and faltering growth and mothers who are struggling to make enough milk. Pamela speaks passionately on breastfeeding and is a well-loved mentor and friend to many in the lactation field.

As a nurse and an International Board Certified Lactation Consultant (IBCLC), I have the opportunity to work with nearly every pregnant woman and new mom and baby at a group of four primary care health centers in Northern California. I would like to share my experience, concerns and request for collaboration to closely examine the new practice of placenta encapsulation, as it has grown to become a component of the postpartum experience for the new moms whom I work with and throughout the United States. I have encountered assumptions that placenta consumption increases milk production, is a prevention for postpartum depression, and has existed in history as an ancient human practice. I will provide a summary here of the work I do and what I have found with my clients involving this practice.

As a nurse and an International Board Certified Lactation Consultant (IBCLC), I have the opportunity to work with nearly every pregnant woman and new mom and baby at a group of four primary care health centers in Northern California. I would like to share my experience, concerns and request for collaboration to closely examine the new practice of placenta encapsulation, as it has grown to become a component of the postpartum experience for the new moms whom I work with and throughout the United States. I have encountered assumptions that placenta consumption increases milk production, is a prevention for postpartum depression, and has existed in history as an ancient human practice. I will provide a summary here of the work I do and what I have found with my clients involving this practice.