Factors that influence where babies sleep in the United States.

Kathleen Kendall-Tackett, PhD, IBCLC, RLC, FAPA, Zhen Cong, PhD, Thomas Hale, PhD

This study was published in 2016 in Clinical Lactation, 7(1),18–29.

The impact of feeding method, mother’s race/ethnicity, partner status, employment, education, and income

Overview: Bedsharing is common in the United States in spite of numerous public health campaigns telling parents not to do it. This suggests that generic, never-bedshare messaging does not result in safe-sleep behavior. It also suggests we know little about the characteristics of mothers who bedshare. This study addresses the gap by examining demographic characteristics of mothers including race/ethnicity, income, education, partner status, and maternal age.

Sample: The sample was the U.S. cohort (N = 4,789) of the Survey of Mothers’ Sleep and Fatigue.

Results: Consistent with previous findings, we found that African American and American Indian mothers were more likely to bedshare, as were lower income and single mothers. We also found that bedsharing mothers were more likely to have lower education levels, be younger age at first birth, and were less likely to be currently employed. There were also striking racial/ethnic differences on location of night feeds, where mothers think babies should sleep, and their reasons for engaging in their nighttime parenting practices.

Conclusion: Our findings suggest that the mothers’ demographics are related to bedsharing practices. Furthermore, simply describing bedsharing in terms of “cultural differences” oversimplifies a complex set of behaviors and beliefs. Safe sleep messaging, including safe bedsharing, needs to be tailored to address the various subgroups of mothers living in the United States.

Key words: bedsharing, mother–infant, race/ethnicity, partner, income, education, maternal age.

In the United States, most parents sleep with their babies at least part of the night, a behavior that persists even when public health campaigns specifically tell them not to (Kendall-Tackett, Cong, & Hale, 2010). In one study, with a sample of 1,867 mothers from Oregon, Lahr, Rosenberg, and Lapidus (2007) found that 76% of mothers bedshare at least some of the time. These findings were based on Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System (PRAMS) data collected in 1998–1999, before the current controversy or policy recommendations (Lahr et al., 2007). More recently, in the U.S. sample of the Survey of Mothers’ Sleep and Fatigue (N = 4,789), approximately 60% of babies ended the night in their parents’ bed (Kendall-Tackett et al., 2010).

In the United States, most parents sleep with their babies at least part of the night, a behavior that persists even when public health campaigns specifically tell them not to (Kendall-Tackett, Cong, & Hale, 2010). In one study, with a sample of 1,867 mothers from Oregon, Lahr, Rosenberg, and Lapidus (2007) found that 76% of mothers bedshare at least some of the time. These findings were based on Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System (PRAMS) data collected in 1998–1999, before the current controversy or policy recommendations (Lahr et al., 2007). More recently, in the U.S. sample of the Survey of Mothers’ Sleep and Fatigue (N = 4,789), approximately 60% of babies ended the night in their parents’ bed (Kendall-Tackett et al., 2010).

Simply telling parents not to bedshare does not appear to change their behavior. Rather, it drives parents’ nighttime behavior underground. Because parents cannot talk with their healthcare providers about nighttime feeding and parenting, they often improvise and do things that are genuinely dangerous, such as sleeping on the couch with their babies (Kendall-Tackett et al., 2010). The interesting question is why this occurs. To encourage safe behavior, we need to understand parents’ nighttime parenting behavior.

Bedsharing and breastfeeding

Why do so many mothers bedshare? Breastfeeding is one obvious answer. For example, an ethnographic study of 200 mothers found that bedsharing was a “natural result” of frequent nighttime feeding (McKenna & Volpe, 2007). Mothers indicated that they were bedsharing even when they had initially planned to have their babies sleep in a crib. McKenna and Volpe noted that the ease of nighttime breastfeeding, and the emotional security bedsharing provided, made it the most practical arrangement for parents in their study.

Other recent studies found that mothers who bedshare breastfeed longer and are more likely to breastfeed exclusively. For example, Ball (2007) conducted a longitudinal study of 97 initially breastfed infants over the first year. Bedsharing infants were twice as likely to still be breastfeeding compared to infants who were not bedsharing. Similarly, a longitudinal study of 14,062 families in Avon, United Kingdom, found that bedsharing, in all its variations, was significantly related to higher rates of breastfeeding at 12 months (Blair, Heron, & Fleming, 2010).

The relationship between bedsharing and breastfeeding is so strong and consistent that even sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS) researchers are noting it. “Advice on whether bed sharing should be discouraged needs to take into account the important relationship with breastfeeding” (Blair et al., 2010, p. e1119).

Demographic factors related to bedsharing

A great deal of effort and money has been devoted to safe-sleep messaging that has not changed behavior. Public health officials have made assumptions about the populations they target, but these assumptions have not been tested empirically. Without this information, and without understanding the complexity of mother-infant sleep, it is difficult to design a public health campaign that will actually be effective in promoting safe sleep, including safe bedsharing.

Regarding bedsharing, opponents of the practice often assume that it is something only poor, ethnic minority families do. For example, in a statement regarding a SIDS prevention program designed to give cribs to poor families, James Kemp noted that “babies in poor families tend to share beds, either with parents or other children.” In other words, families bedshare because they are too poor to have cribs. Is that true? We don’t actually know. In fact, we know little about the demographics of bedsharing families.

Of all demographic variables, race/ethnicity has been studied the most. Bedsharing rates tend to be higher in ethnic minority groups, such as African Americans and Latinas. For example, the Lahr et al. (2007) study, using PRAMS data from Oregon, found that 43% of Black mothers indicated that they “always” bedshare compared to 16% of Whites (Lahr et al., 2007). Lahr et al. found that middle- and upper-class racial/ethnic minority families also had high rates of bedsharing, suggesting that there were cultural reasons for bedsharing rather than it simply being a matter of not being able to afford a crib. From that finding, we might conclude that income does not impact bedsharing rates. However, in that same data set, Lahr et al. noted that mothers were more likely to bedshare if they breastfed longer than 4 weeks, had a household income of less than $30,000, or were single. These findings suggest that demographic factors are related to bedsharing.

This study addresses the gap in the literature. Using data from the Survey of Mothers’ Sleep and Fatigue (Kendall-Tackett et al., 2010), we sought to answer some basic questions about demographic characteristics of families who bedshare with a large sample of mothers from the United States (N = 4,789). The present analyses will examine breastfeeding rates and the following characteristics: race/ethnicity, partner status, mother’s age, mother’s employment status, household income, and mother’s education level. The goal is to understand more about families who bedshare so that messaging about safe sleep (such as avoiding sleep on the sofa) can be more accurately targeted.

Method

Study participants. The data included in this analysis were from the U.S. mothers (N = 4,789) who participated in the Survey of Mothers’ Sleep and Fatigue in 2008–2009. The total sample from this study was 6,410 mothers of babies 0–12 months old, representing 59 countries. The demographic characteristics of the U.S. sample are listed on Table 1.

Study participants. The data included in this analysis were from the U.S. mothers (N = 4,789) who participated in the Survey of Mothers’ Sleep and Fatigue in 2008–2009. The total sample from this study was 6,410 mothers of babies 0–12 months old, representing 59 countries. The demographic characteristics of the U.S. sample are listed on Table 1.

Sample recruitment. The sample was recruited via announcements and flyers distributed to Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) breastfeeding coordinators, U.S. Breastfeeding Coalition coordinators, lactation consultants, and La Leche League Leaders. The investigators described the study and asked for assistance in recruiting mothers. Flyers and cards were distributed electronically and via hard copy, with a Web link for the survey. This survey was open to all mothers with babies 0–12 months of age.

Survey development. The research questions were taken from the 253-item Survey of Mothers’ Sleep and Fatigue. The questions were predominantly close-ended in format and were developed for this study via open-ended interviews with mothers and feedback from mothers and healthcare providers.

Bedsharing was measured by the following question: “Where does your baby end the night?” We selected this question for our analyses based on our previous study (Kendall-Tackett et al., 2010); this question yielded the highest percentages of families saying that they were bedsharing and we believed that it more accurately measured the behavior.

Breastfeeding was measured by a single item used in previous analyses: “Since your baby was born, have you breastfed, formula-fed, or both breast and formula fed?” Mothers who indicated that they breastfed/were breastfeeding were classified as “breastfeeding only.” We used this term, rather than “exclusive breastfeeding” because exclusive breastfeeding is a more stringent definition (i.e., never received supplements), which the item in this study did not capture.

Data collection. Data were collected via an online survey that was available on the Texas Tech University Department of Pediatrics website. A screening question asked for the baby’s age. If the response was 12 months or less, the mother was allowed to continue the survey. The survey and data collection procedure was reviewed and approved by the Texas Tech University School of Medicine Institutional Review Board.

Results and discussion

Although bedsharing is common across all demographic categories, there were some differences based on feeding method, race/ethnicity, income, partner status, employment status, and mother’s age.

Feeding method. Consistent with previous studies, mothers who were bedsharing were significantly more likely to be breastfeeding only. The more formula an infant received, the more likely they were to be sleeping in a separate place, either in the parents’ room or in a different room,

x² (2) = 393.55, p < .000. See Figure 1.

Mother’s race/ethnicity. We found that mothers’ race/ethnicity was associated to several behaviors related to nighttime feeding. These findings are somewhat preliminary because of the relatively small number of mothers in some ethnic groups, but they highlight some interesting differences.

Consistent with previous findings, African American infants were significantly more likely to bedshare. Mothers who identified as multiethnic or American Indian were also more likely to bedshare. A surprisingly high number of White mothers were bedsharing in our data, in contrast to previous studies. This finding may have been because of the way the question was worded: “Where does your baby end the night?” When parents were asked where their babies ended the night, they were twice as likely to admit that they were bedsharing compared to when asked “Where does your baby usually sleep?” (Kendall-Tackett et al., 2010).

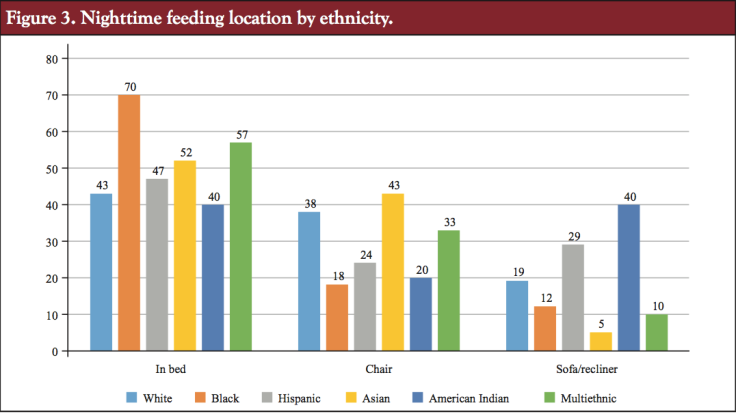

In contrast to Lahr et al. (2007) findings, Hispanic and Asian mothers had the lowest rates of bedsharing, x² (5) = 14.82, p < .011. See Figure 2. There were also racial/ethnic differences in night feeding in a chair in the mother’s bedroom, or on a sofa or recliner. Asian and White mothers were more likely to be feeding their babies in a chair in their bedrooms. American Indian mothers were most likely to feed their babies on sofas or recliners. These findings suggest that safe sleep messaging designed to present the same message to all mothers is not likely to be effective because they engage in very different patterns of behavior.

It is also interesting to note that African American mothers are most likely to feed their babies in bed and least likely to feed their babies on unsafe surfaces. So although Black mothers are often the focus of antibedsharing campaigns, they are also the ones most in line with at least part of the guidance offered by the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP).

Because of the extremely high risk of SIDS and suffocation on couches and armchairs, infants should not be fed on a couch or armchair when there is a high risk that the parent might fall asleep . . . . In recent years, the concern among public health officials about bedsharing has increased because there have been increased reports of SUIDs occurring in high-risk sleep environments, particularly bedsharing and/or sleeping on a couch or armchair . . . Therefore, if the infant is brought into the bed for feeding, comforting, and bonding [emphasis added], the infant should be returned to the crib when the parent is ready for sleep. (American Academy of Pediatrics & Task Force on Sudden Infant Death Syndrome, 2011) See Figure 3.

Racial/ethnic differences in beliefs about bedsharing. We also examined some beliefs around bedsharing. Many have assumed that higher bedsharing rates in racial/ethnic minority communities are because of “cultural beliefs” that favor bedsharing. To assess this, we asked mothers where they thought babies should sleep and where their partners thought babies should sleep. Surprisingly, Hispanic, Black, and Asian mothers were the least likely to say that babies should sleep in their mothers’ beds, even though they typically have the highest rates. There was a similar pattern with women’s partners. Partners of Asian and Hispanic women were also the least likely to say that babies should sleep with their mothers. See Figure 4.

Racial/ethnic differences in reasons for nighttime parenting practices. Given some of the surprising racial/ethnic differences we found, we asked mothers about two possible reasons for bedsharing: “it was the only thing that worked” and “it was the right thing to do.” For many of the racial/ ethnic minority mothers, pragmatic concerns (“only things that worked”) trumped ideology (“right thing to do”) when deciding where their babies sleep. See Figures 5 and 6.

We urge some caution, however, regarding our findings in that our sample size for these various groups is still relatively small. Research with larger samples will need to be done. But our findings suggest that the intersection of race/ethnicity and sleep location is more complex than it appeared in earlier studies and there doesn’t appear to be one uniform pattern of “cultural beliefs” that support bedsharing.

Mother’s partner status. The Lahr et al. study (2007) suggested that mothers were more likely to bedshare if they were single versus married/partnered. Our findings are consistent with that previous study. Mothers were more likely to bedshare if they were not living with a partner, across all income levels, x² (1) = 11.53, p < .001. See Figure 7.

Mother’s age. Mother’s age is a demographic factor that has never been studied with regard to bedsharing, but given previous findings on single and lower income mothers being more likely to bedshare, we might predict that younger mothers were more likely to bedshare. That hypothesis was partially supported. When we examined mothers’ current age, there was no significant difference with regard to infant sleep location, F(1, 6.19) = .275, p = .60. However, age at first birth was significantly related to sleep location. Mothers who were younger at their first birth were significantly more likely to bedshare, F(1, 2233.78) = 86.92, p < .000. This could be because younger mothers were more likely to be single/low income. Or it could reflect that younger mothers were more open to “alternative” methods of childrearing. See Figure 8.

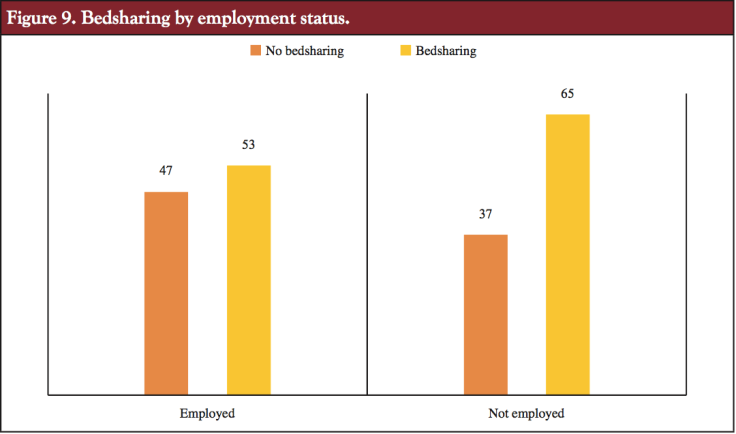

Mother’s employment status. Mother’s employment status was another factor potentially related to infant sleep location. Anecdotally, mothers will frequently cite needing to get up for work the next morning as a reason for bedsharing. Given that, we might expect that employed mothers were more likely to bedshare. Our findings indicate the opposite: Mothers not currently employed were more likely to bedshare, x²(1) 5 63.23, p < .000. See Figure 9.

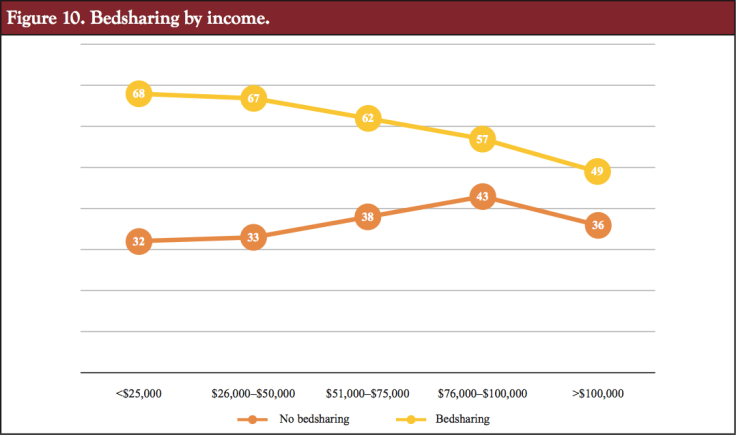

Mother’s income. The Lahr et al. study (2007) found that lower income mothers were most likely to bedshare. Our findings are similar. Although a substantial percentage of mothers at all income levels are bedsharing, significantly more low-income mothers bedshare. These findings are consistent with factors such as employment status, age at first birth, and education level, x² (4) = 114.33, p < .000. See Figure 10.

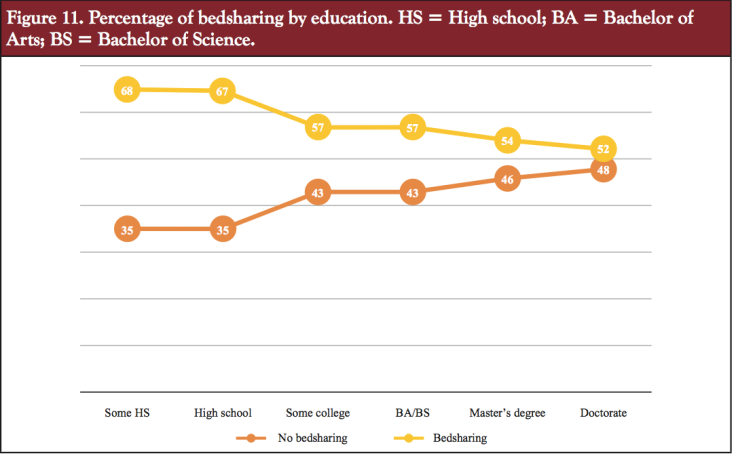

Mother’s education. The final variable we examined was mother’s education level. We found that the higher the mother’s education levels, the less likely she was to bedshare, x²(4) = 52.07, p < .000. Interestingly, in an earlier article, we found that high education and income were related to highly dangerous sleep behavior, such as nighttime feeding in a chair or recliner, a behavior with a high risk of infant mortality (Kendall-Tackett et al., 2010). See Figure 11.

Clinical implications. Our findings suggest that safe sleep messaging cannot be accomplished with sound bites and catchy slogans. Mother-infant sleep is complex. People bedshare for a wide range of reasons that are both ideological and pragmatic. A critical issue for these messages to address is the issue of where babies feed at night. When speaking to families, practitioners should ask about where they feed their babies and where their babies are when the mothers fall asleep. Practitioners can brainstorm with parents about ways to ensure that babies are safe when mothers fall asleep. Especially concerning was the high percentage of mothers in our previous study (Kendall-Tackett et al., 2010) who reported falling asleep on the sofa or recliner with their babies, because these are the most dangerous of all sleep locations for babies.

When speaking to parents, here are suggested questions you can ask.

“I want to ask you some questions about where your baby sleeps.”

- Where does your baby end the night?

- Where else does your baby sleep at night and during the day?

- Can you tell me more about the sleep surfaces? Are there any pillows, covers, or toys where your baby sleeps?

- What position does your baby usually sleep in? Tummy, side, or back?

- Where do you feed your baby at night? Do you sometimes fall asleep there?

These questions will cover the basics of safe sleep, giving you an opportunity to assess the safety of the baby’s sleep locations. It’s important to emphasize the safety of all sleep locations: firm mattress, no fluffy bedding, pillows, or toys. And sleeping with a baby on a recliner, sofa, or chair is never a safe option, so that it is important to talk with parents about not feeding babies in these locations when there is a chance that they may fall asleep, per AAP guidelines (American Academy of Pediatrics & Task Force on Sudden Infant Death Syndrome, 2011).

If institutions prohibit practitioners from discussing safe bedsharing with parents, another option is to discuss alternatives to cribs that are still near parents, such as cosleepers or Moses’ baskets in the parents’ bed. These arrangements not only keep babies near but also provide them with a separate sleep surface. These arrangements may be the type of compromise necessary to move the conversation forward about safe sleep options for all parents.

Conclusions

Our findings suggest that infant sleep and reasons for parents’ behaviors are more complicated than we have believed. Their practices are not simply a matter of “cultural differences.” We found that African American and American Indian mothers are most likely to bedshare. Bedsharing mothers were more likely not to be breastfeeding only, but also had lower incomes and less education, were younger at their first births, not currently employed, and not living with a partner. These demographics suggest that one-size-fits-all safe sleep messaging will not be effective. There are many factors that influence where babies sleep. If we are going to help mothers be safe in their sleeping choices, we need to first understand what is influencing them and why mothers make the choices they do. We also need to be mindful of providing safe sleep information in such a way that it does not undermine breastfeeding. That will mean providing families with information on safe sleep for all sleep locations, including bedsharing.

Our findings suggest that infant sleep and reasons for parents’ behaviors are more complicated than we have believed. Their practices are not simply a matter of “cultural differences.” We found that African American and American Indian mothers are most likely to bedshare. Bedsharing mothers were more likely not to be breastfeeding only, but also had lower incomes and less education, were younger at their first births, not currently employed, and not living with a partner. These demographics suggest that one-size-fits-all safe sleep messaging will not be effective. There are many factors that influence where babies sleep. If we are going to help mothers be safe in their sleeping choices, we need to first understand what is influencing them and why mothers make the choices they do. We also need to be mindful of providing safe sleep information in such a way that it does not undermine breastfeeding. That will mean providing families with information on safe sleep for all sleep locations, including bedsharing.

References

American Academy of Pediatrics & Task Force on Sudden Infant Death Syndrome. (2011). Policy Statement: SIDS and other sleep-related deaths: Expansion of recommendations for a safe infant sleeping environment. Pediatrics, 128(5), 1030–1039. doi:10.1542/peds.2011-2284

Ball, H. L. (2007). Bed-sharing practices of initially breastfed infants in the first 6 months of life. Infant and Child Development, 16(4), 387–401. doi:10.1002/icd.519

Blair, P. S., Heron, J., & Fleming, P. J. (2010). Relationship between bed sharing and breastfeeding: Longitudinal, population-based analysis. Pediatrics, 126(5), e1119–e1126. doi:10.1542/peds.2010-1277

Kendall-Tackett, K. A., Cong, Z., & Hale, T. W. (2010). Mother- infant sleep locations and nighttime feeding behavior: U.S. data from the Survey of Mothers’ Sleep and Fatigue. Clinical Lactation, 1(1), 27–30. doi:10.1891/215805310807011837

Lahr, M. B., Rosenberg, K. D., & Lapidus, J. A. (2007). Maternal-infant bedsharing: Risk factors for bedsharing in a population-based survey of new mothers and implications for SIDS risk reduction. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 11(3), 277–286.

McKenna, J. J., & Volpe, L. E. (2007). Sleeping with baby: An internet-based sampling of parental experiences, choices, perceptions, and interpretations in a Western Industrialized context. Infant and Child Development, 16(4), 359–385. doi:10.1002/icd.525

Kathleen Kendall-Tackett is a health psychologist and International Board Certified Lactation Consultant, and the owner and Editor-in-Chief of Praeclarus Press, a small press specializing in women’s health. She is Editor-in-Chief of two peer-reviewed journals: Clinical Lactation and Psychological Trauma. She is Fellow of the American Psychological Association in Health and Trauma Psychology, Past President of the APA Division of Trauma Psychology, and a member of the Board for the Advancement of Psychology in the Public Interest. Dr. Kendall-Tackett specializes in women’s-health research including breastfeeding, depression, trauma, and health psychology, and has won many awards for her work including the 2016 Outstanding Service to the Field of Trauma Psychology from the American Psychological Association’s Division 56. Her websites are:

Kathleen Kendall-Tackett is a health psychologist and International Board Certified Lactation Consultant, and the owner and Editor-in-Chief of Praeclarus Press, a small press specializing in women’s health. She is Editor-in-Chief of two peer-reviewed journals: Clinical Lactation and Psychological Trauma. She is Fellow of the American Psychological Association in Health and Trauma Psychology, Past President of the APA Division of Trauma Psychology, and a member of the Board for the Advancement of Psychology in the Public Interest. Dr. Kendall-Tackett specializes in women’s-health research including breastfeeding, depression, trauma, and health psychology, and has won many awards for her work including the 2016 Outstanding Service to the Field of Trauma Psychology from the American Psychological Association’s Division 56. Her websites are:

Zhen Cong, PhD, is associate professor of Human Development and Family Studies at Texas Tech University in Lubbock, Texas. She is associate editor for statistic for the journal Psychological Trauma. Her research interests include aging, migration, intergenerational relations, grandparenting, and the psychosocial impact of disasters.

Zhen Cong, PhD, is associate professor of Human Development and Family Studies at Texas Tech University in Lubbock, Texas. She is associate editor for statistic for the journal Psychological Trauma. Her research interests include aging, migration, intergenerational relations, grandparenting, and the psychosocial impact of disasters.

Thomas W. Hale, PhD, is professor of pediatrics at Texas Tech University School of Medicine, Amarillo, Texas. He is also assistant dean of Research, director of the clinical research unit, and director of the Infant Risk Center.

Thomas W. Hale, PhD, is professor of pediatrics at Texas Tech University School of Medicine, Amarillo, Texas. He is also assistant dean of Research, director of the clinical research unit, and director of the Infant Risk Center.

Sleep Awareness on Women’s Health Today

Controlled Crying and Long-Term Harm

Four Reasons Our Sleep Is Being Disturbed

Help for Very Fatigued New Mothers

How Do Mothers Get More Sleep?

Lying Down to Breastfeed: Mother and Baby Sleep Positions

Answers to 5 Common Questions

Answers to 5 Common Questions

September 8, 2017 at 4:24 pm

Interesting data. Perhaps white mothers are reluctant to admit they are bedsharing because so many peds are against it here in the U.S. I also think this study neglects parenting and religious values and philiophies. Perhaps asking what type of parenting style monthers idenitify with (e.g. Attachments, CIO, etc…) would shed light on bed sharing behaviors.

LikeLike